(image http://www.rhs.org.uk)

Scientists disagree about things constantly. It is part of the very nature of studying science to constantly question and re-examine the data. Even the most well-studied, comprehensively validated, scientific principles will have their opponents. Many different types of experiment will be carried out by lots of different scientists before we will start to think of something as scientifically true. However, even then there will be someone, somewhere who disagrees. When people say that even scientists can’t agree on whether we are bringing about climate change through our own actions or, for that matter, whether autism is caused by the MMR vaccine, what is actually happening is that a single scientist (or a couple of scientists) has put forward an idea (usually through publishing a scientific paper) that is then disproven by the scientific community after rigorous experiments have been performed.

Within science, we see this happen from time to time when scientific papers are published and the data cannot be replicated. In some cases, the scientist doing the initial work has falsified data but often it is a less sinister situation of data misinterpretation or poorly carried out experiments. The real danger comes when this scientist is unwilling to let go of their original hypothesis, even in the face of mounting, irrefutable evidence to the contrary. This is especially damaging when the research is of interest to a general audience. It can be almost impossible to change the minds of politicians and the public once there is an impression of disagreement amongst the scientific community.

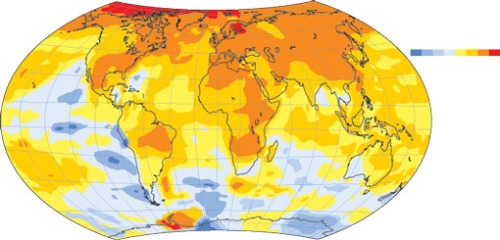

When politicians or members of the public question why it is so hard to find scientists to argue against the idea of man-made climate change, the answer is because there essentially aren’t any. Scientists virtually unanimously believe that the planet is warming, that it is at least partially our fault, and that the consequences are likely to be devastating. Whatever experiments are done, whatever measurements are taken, and whatever predictions are made, many people seem to be unbudgeable from the idea that scientists are trying to deceive them and that climate change is a myth. Whether we are responsible for climate change is still a matter of some debate, but global warming is a fact and the argument that scientists generally disagree about this is simply untrue.